The name I have always used for this plant is ‘Jack by the Hedge’ but the accepted English name is now ‘Garlic Mustard’. It is another spring flower that seems to ‘spring’ from nowhere at this time of year. Once the temperatures increase around April it grows rapidly, and soon forms conspicuous and rather attractive colonies by hedges and roadsides, each erect stem carrying a small bouquet of brilliant white flowers.

Alliaria petiolata, with flowers and fruits. Fairy foxglove in the background. Image: Chris Jeffree.

It is a native in all European countries and was first recorded in Britain by William Turner (known as ‘The father of English botany’) in 1538. It occurs in several habitats here: hedgerows, woodland edges, embankments, shingle, and waste ground. In Scotland it is a common component of the urban flora, often along roads and in parks. It is a minor medicinal plant but has been much-used in the kitchen for its delicate garlic flavour. It was such a useful plant that European settlers took seeds to wherever in the world they went. In North America it was recorded in the 1860s in Long Island, New York, and it reached Toronto in Canada in 1879. In both USA and Canada it is regarded as an invasive alien. Here in Europe it is not a serious weed but a welcome sign of spring.

A. petiolata. Seeds are dispersed over only short distances and hence the rather crowded clumps of offspring are typical of the species. Image: Chris Jeffree.

It takes two years to complete its life cycle. Seeds germinate in late winter or spring, and young plants form rosettes of small leaves. During the first year it develops a tap root and the following spring it mobilises the stored materials to grow rapidly, forming flowers from April to June and shedding seeds from July onwards (Cavers at al. 1979).

Seedlings and mature plants, Water of Leith, Canonmills, Edinburgh on 18/5/23. Images: John Grace.

Other names are garlic root, hedge garlic, sauce-alone, jack-in-the-bush, penny hedge and poor man’s mustard. The garlic smell is most obvious when young leaves are crushed.

It belongs to the Family of cabbages and mustards, the Brassicaceae, with the four petals and sepals forming a cross (the old Family name is Cruciferae – from Latin, meaning ‘bearing a cross’). Plants of this family contain glucosinolates, a class of organic chemicals which form pungent compounds when cells are crushed and the glucosinolates come into contact with enzyme myrosinase (stored in a separate cell compartment). The most pungent-flavoured of all its members have become global culinary celebrities (wasabi, horseradish and the mustards) whilst others are milder (radishes and brussel sprouts). Garlic Mustard is one of the milder, and much used for sauces and salads in former times, particularly in sauces for fish. Perhaps sauces were the main use, as John Gerard writing in 1597 has its name as Sauce-Alone, or Jack-of-the-Hedge.

Details of flowers: 4 petals, 4 sepals and 4-6 stamens. Image: Chris Jeffree.

The glucosinolates are for chemical defence, but anyone who grows cabbages in their garden will notice that caterpillars of the white butterfly (Pieris rapae Family Pieridae) are nevertheless able to consume the plants. They have evolved protective chemical weapons to overcome the defender. In the case of Garlic Mustard the caterpillars are those of the related Orange Tip butterfly (Anthocharis cardamines, in the Family Pieridae) which generally eat the long green seed-pods, which they themselves resemble. Altogether, 69 insect herbivores have been recorded, including some beetles, weevils and moths.

For readers interested in chemistry. Compound 1 is the glucosinolate. The glucose part (2) is broken off by the enzyme myrosinase. The mustard oil (3) is the sulphur-containing cyanide-like part that constitutes the chemical ‘weapon’ of the plant, called isothiocyanate and known as mustard oil or more properly the volatile oil of mustard. The blue R indicates ‘the Rest of the Molecule’, an additional structure that can vary. Credit: Jü, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to several researchers, the soil is also a chemical battle-ground. It has been claimed that Garlic Mustard produces chemical compounds in the soil which inhibit germination of other species, and may also have an antagonist effect on soil fungi. The evidence seems contradictory (Cipollini 2016), or at least it seems to depend on the experimental context. Such phenomena are called allelopathy, and are not uncommon among many groups of plants.

Adult and larva of Orange Tip butterfly (Anthocharis cardamines) on A. petiolata. Images: Chris Jeffree.

The species is rapidy invading North America, and reducing biodiversity in forests; at least that is the impression gained by searching ‘Alliaria petiolata’ using Google Scholar. The search engine finds 13,500 research papers, most of which are by North American authors and begin by stressing what a troublesome weed this alien species has become. I was surprised to find this, as the plant is benign here in Britain. It is however not uncommon for plant species to thrive better when they reach new territory. There are several hypotheses about how this might come about. The most popular of these is that the natural enemies of the plant (mostly insect herbivores) are absent in the new location. Like humans, plants flourish best when not engaged in continuous warfare. For an up-to-date discussion of this intriguing hypothesis, see Rodgers et al (2022).

The distribution pattern in Britain and Ireland shows the species is widespread except for in the north and west. It seems to be most abundant in highly populated regions and so the absence in the west may reflect its lesser culinary use in past times. The pattern has not changed much over recent decades. It tolerates shade quite well, but in Britain it rarely invades woodlands, sticking to edges. It thrives in fertile soils and avoids acidic substrates.

Distribution in Britain and Ireland. From BSBI/maps.

The genus name Alliaria refers to the flavour and smell being like that of Allium, the genus of onion and garlic. The old name was Alliaria officinalis. Plants with the name ‘officinalis’ or ‘officinale’ are those that belong to the medicine-cupboard.

In fact, the medicinal use is rather minor. Gerard’s Herbal says there are none. But the website Plants for the Future finds many

“The leaves have been taken internally to promote sweating and to treat bronchitis, asthma and eczema. Externally, they have been used as an antiseptic poultice on ulcers etc, and are effective in relieving the itching caused by bites and stings. The leaves and stems are harvested before the plant comes into flower and they can be dried for later use. The roots are chopped up small and then heated in oil to make an ointment to rub on the chest in order to bring relief from bronchitis. The juice of the plant has an inhibitory effect on Bacillus pyocyaneum and on gram-negative bacteria of the typhoid-paratyphoid-enteritis group. The seeds have been used as a snuff to excite sneezing”.

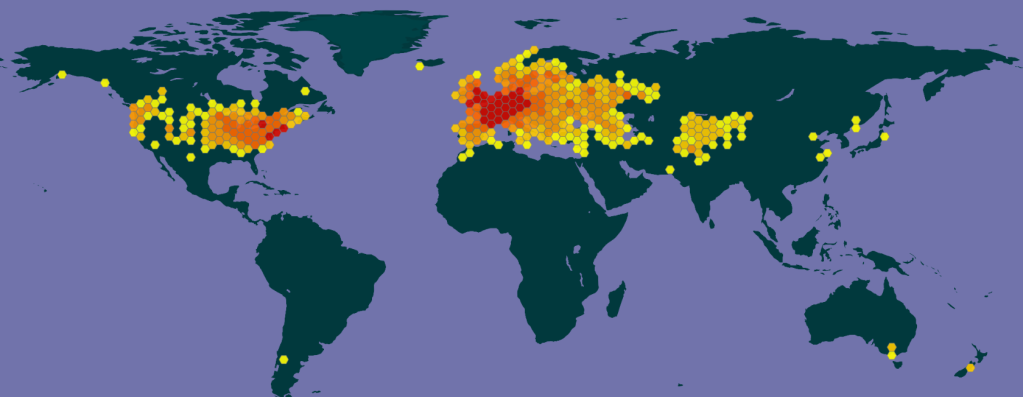

Global distribution, from GBIF.

Look out for first-year seedlings of this plant. Over the summer, you may see fresh green heart-shaped leaves at the base of a wall or on road verges. They can be quite large. Crush the leaves and smell them. If they smell of garlic they must be Alliaria petiolata. They will flower next year.

References

Cavers PB et al (1979)The biology of Canadian weeds. 35. Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieb.) Cavara and Grande. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 59, 217-229.

Cipollini D (2016) A review of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata, Brassicaceae) as an allelopathic plant. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, 143, 339-348.

Rodgers VL et al. (2022) Where Is Garlic Mustard? Understanding the Ecological Context for Invasions of Alliaria petiolata. BioScience 72, 521-537.

©John Grace