Some artists express their age so perfectly that looking at their work is like travelling in a time machine. Jean-Etienne Liotard is one of those redeemers of lost time. His art is a lace-framed photograph of the Enlightenment.

If you think the 18th century was all wigs, toffs and hangings, the subtle radicalism of Liotard’s art should change your mind. The 1700s were an age of revolution in life and thought. The violent climax of that revolution is foreseen here, eerily, in a portrait of the future Queen Marie Antoinette of France when she was a seven-year-old Austrian princess. She looks assured and confident. She will die at the guillotine.

The values Liotard portrays and embodies are those of reason and curiosity. The Enlightenment was an era that saw itself as spreading science and liberating thought – “enlightening” the continent of Europe. The people in his paintings are curious, exploratory, open-minded. English aristocrats dress in Turkish clothes. Women pose reading, relaxed and self-possessed. A married couple beam at each other from companion portraits that celebrate the new ideal of loving marriage.

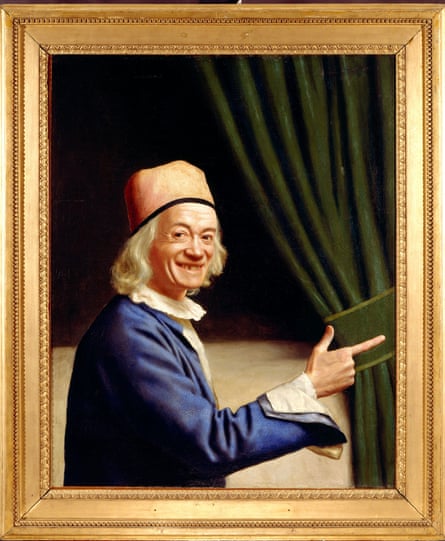

Smiles are everywhere. Liotard himself cracks a joyous face in his Self Portrait Laughing, painted in about 1770. He looks like a cackling monkey with long white hair. Or rather, he looks like the philosopher Voltaire, author of Candide and ruling intellect of this rational age, who the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon was to portray smiling in a work made eight years after Liotard’s self-portrait. Liotard is a pioneer of Enlightenment art – the smile, such a rarity in traditional portraiture (that’s why the Mona Lisa is so unusual) presides over this show with its message of benevolence, civil decency and good sense.

And his smiling art is made sunnier still by his use of pastels. Many of the portraits here were executed not with paint but pastel crayons, often on vellum. It is a delicious technique. Liotard’s mastery of drawing with crayon lets him give people the most electric blue and red silk garments, the most subtly blushing cheeks. The colours and frilly details of the fine clothes people wear – from kaftans to elaborate waistcoats – are almost surreal in their sensuality. The eye can wander for ages in his sitters’ rumpled valleys of fine material.

Yet there’s a kick to these portraits. They glow with pastel warmth, but are ruthlessly realistic. After a while you start to notice that no one here is very beautiful. Or rather, no one is given the ideal beauty that was conventional in art. Everyone is real – and reality means big noses, square jaws and disarming poses. Princess Louisa Anne, ailing daughter of the Prince of Wales, stares at the artist, lost and dazed and haunting. The ruler of Moravia sits tightly grasping the arms of an archaic looking throne, anxious in her lonely kingdom.

The world is changing. Reason rules. People are getting free in their behaviour. A grateful patient poses paying homage to a classical bust of the doctor who cured her – medicine is becoming a science. Liotard draws the divan in his house in Istanbul, where he lived for four years, assimilating eastern ways, portraying local people and European visitors with the encouragement of Sir Everard Fawkener, British ambassador to the Sublime Porte, who Liotard portrays in his oriental finery.

The clarity of Liotard’s calm, exact, absolutely honest art is a beacon of the Enlightenment. He looks patiently at a bowl of fruit, a Chinese tea service, a young woman carefully carrying a pot of hot chocolate. The world is solid and scientific and he rejoices in it. Real life is wonderful. It makes Liotard smile.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion